Jerusalem Burial Cave Reveals: Names, Testimonies of First Christians

by Jean Gilman

JERUSALEM, Israel – Does your heart quicken when you hear someone give a personal testimony about Jesus? Do you feel excited when you read about the ways the Lord has worked in someone’s life?

|

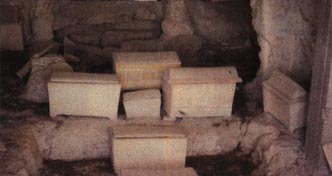

The first century catacomb, uncovered by archaeologist P. Bagatti on the Mount of Olives, contains inscriptions clearly indicating its use, “by the very first Christians in Jerusalem.” |

If you know the feeling of genuine excitement about the workings of the Lord, then you will be ecstatic to learn that archaeologists have found first-century dedications with the names Jesus, Matthias and “Simon Bar-Yonah” (“Peter son of Jonah”) along with testimonials that bear direct witness to the Savior.

|

A “head stone”, found near the entrance to the first century catacomb, is inscribed with the sign of the cross. |

Where were such inscriptions found? Etched in stone – in the sides of coffins found in catacombs (burial caves) of some first-century Christians on a mountain in Jerusalem called the Mount of Olives.

|

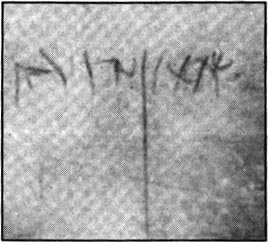

An inscription, found on a first century coffin bearing the sign of the cross, reads: “Shimon Bar Yonah” = “Simon [Peter] son of Jonah”. |

Like many other important early Christian discoveries in the Holy Land, these major finds were unearthed and the results published many decades ago. Then the discoveries were practically forgotten. Because of recent knowledge and understanding, these ancient tombs once again assume center stage, and their amazing “testimonies in stone” give some pleasant surprises about some of the earliest followers of Jesus.

The catacombs were found and excavated primarily by two well-known archaeologists, but their findings were later read and verified by other scholars such as Yigael Yadin, J. T. Milik and J. Finegan.

|

The ossuaries (stone coffins), untouched for 2,000 years, as they were found by archaeologist P. Bagatti on the Mt. of Olives. |

The first catacomb found near Bethany was investigated by renowned French archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau. The other, a large burial cemetery unearthed near the modern Dominus Flevit Chapel, was excavated by Italian scholar, P. Bagatti.

Both archaeologists found evidence clearly dating the two catacombs to the first century AD, with the later finding coins minted by Governor Varius Gratus at the turn of the millenium (up to 15/16 AD). Evidence in both catacombs indicated their use for burial until the middle part of the first century AD, several years before the New Testament was written.

The first catacomb was a family tomb investigated by archaeologist Clermont-Ganneau on the Mount of Olives near the ancient town of Bethany. Clermont-Ganneau was surprised to find names which corresponded with names in the New Testament. Even more interesting were the signs of the cross etched on several of the ossuaries (stone coffins).

As Claremont-Ganneau further investigated the tomb, he found inscriptions, including the names of “Eleazar”(=”Lazarus”), “Martha” and “Mary” on three different coffins.

The Gospel of John records the existence of one family of followers of Jesus to which this tomb seems to belong: “Now a certain man was sick, named Lazarus, of Bethany, the town of Mary and her sister Martha. (It was that Mary which anointed the Lord with ointment, and wiped his feet with her hair, whose brother Lazarus was sick)…” (11:1,2)

John continues by recounting Jesus’ resurrection of Lazarus from the dead. Found only a short distance from Bethany, Clermont-Ganneau believed it was not a “singular coincidence” that these names were found.

He wrote: “[This catacomb] on the Mount of Olives belonged apparently to one of the earliest [families] which joined the new religion [of Christianity]. In this group of sarcophagi [coffins], some of which have the Christian symbol [cross marks] and some have not, we are, so to speak, [witnessing the] actual unfolding of Christianity.”

|

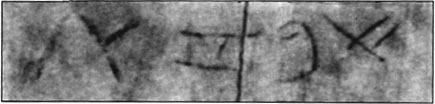

A first-century coffin bearing cross marks as it was found by archaeologist P. Bagatti in the catacomb on the Mt. of Olives. The Hebrew inscription both on the lid and body of the coffin reads: “Shlom-zion”. Archaeologist Claremont-Ganneau found the same name followed by the designation “daughter of Simon the Priest.” |

As Claremont-Ganneau continued to investigate the catacomb, he found additional inscriptions including the name “Yeshua” (=”Jesus”) commemoratively inscribed on several ossuaries. One coffin, also bearing cross marks on it, was inscribed with the name “Shlom-zion” followed by the designation “daughter of Simon the Priest.”

While these discoveries were of great interest, even more important was another catacomb found nearby and excavated by archaeologist P. Bagatti several years later.

|

One of the first-century coffins found on the Mt. of Olives contains a commemorative dedication to: “Yeshua” = “Jesus”. Bagatti also found evidence which clearly indicated that the tomb was in use in the early part of the first century AD. Inside, the sign of the cross was found on numerous first-century coffins.

He found dozens of inscribed ossuaries, which included the names Jairus, Jonathan, Joseph, Judah, Matthias, Menahem, Salome, Simon, and Zechariah. In addition, he found one ossuary with crosses and the unusual name “Shappira” – which is a unique name not found in any other first-century writtings except for the Book of Acts (5:1).

As he continued his excavations, Bagatti also found a coffin bearing the unusual inscription “Shimon bar Yonah” (= “Simon [Peter] son of Jonah”). Other than its existence among the burial tombs of some of the very first Christians, no conclusive evidence was found to identify this stone coffin as that of the disciple and close companion of Jesus, Simon Peter.

However, when Bagatti began excavating the burial place which he numbered 299, he stumbled upon several unique surprises. On ossuary, number 97, which boor the sign of the cross, Bagatti found a Greek inscription.

The inscription was hard to read but could be deciphered: “[Here are the] bones of the younger Judah, a proselyte [to Christianity] from Tyre.” References to Tyre, a port city north of Galilee, is found in Matthew 15 and Mark 7. It was a city visited by Jesus.

Above the inscription, on the same coffin, the Greek letters Chi and Rho were unmistakeably inscribed together, written as a monogram. According to Prof. Jack Finegan of the Pacific School of Religion, Berkeley, who also studied the inscription, this particular monogram was used frequently in Antioch (44AD) and Rome in the first century and was a well known designation for those who were among the first non-Jewish Christians (Acts 11:26).

|

| One of the first-century coffins found on the Mt. of Olives is inscribed with crosses and the unqiue name “Shappira” – a name which is not found in any other first-century writtings except for the Book of Acts (5:1). |

The monogram was written – according to the inscription – on the coffin of a non-Jew, a “proselyte” – that is a pagan who converted to Judaism and Christianity and was later buried in Jerusalem.

Two other coffins – also bearing crosses – were also found not far away and contained a Hebrew inscription which read:”Salome, the proselyte” and a Greek inscription which read: “Diogenes, son of Zena.”

Bagatti concluded that “Diogenes,” a well known Greek name, must have also been a new convert from paganism to Christianity. In all, the evidence clearly pointed to a strong connection between the first Jewish Christians in Jerusalem and those followers of Jesus outside of Israel.

Also found in the same area was another monogram inscription comprised of the Greek letters Iota, Chi, and Beta, which is translated: “Jesus Christ the helper [or redeemer].”

The concept of “helper” or “redeemer” is found in Hebrews 4:16. In addition, early Christian historian, Justin Martyr, said: “For we call Him [Jesus] Helper and Redeemer, the power of whose name even the demons fear.” (Dialogue 30,3)

All together, more than 100 first-century coffins were found on the Mount of Olives, many bearing additional names and cross marks. While not all the remains and inscriptions were preserved well enough to be identified or deciphered, the overall conclusion was clear.

As Prof. Finegan wrote: “[In these tombs], there are signs that can be [considered] Christian, and names that are frequent or prominent in the New Testament… It surely comes within the realm of possibility that at least this area in particular is a burial place of families, some of whose members had become [the very first] Christians.”

Jean Gilman is a staff reporter for the Jerusalem Christian Review. Copyright © 1998 Jerusalem Christian Review. All rights reserved.

This article was reprinted with permission from the Jerusalem Christian Review, Volume 9, Internet Edition, Issue 2.

For more information, please see the Jerusalem Christian Review site.